As thousands of Gazans wait out an uncertain fate on the edge of the Mediterranean, these islands in the Adriatic send their love across the seas, offering up an artistic wedding in absentia. At this year’s Venice Biennale, Palestine looms large.

Hadani Ditmars

The 60th iteration of the iconic art fair has become a set piece for regional tensions, with calls to boycott the Israeli pavilion by ANGA (Art not Genocide Alliance) and the Palestine Museum US followed the decision by Israeli artists and curators to close their own exhibition until a ceasefire materializes. Meanwhile, as Israel and Iran traded fire, Iranian opposition groups called for a boycott of the Iranian pavilion.

For 24-year-old Gazan artist Malak Mattar, whose first solo show in Venice opened recently at the Ferruzzi Gallery across the canal from the Peggy Guggenheim Gallery, “showing my work here feels more urgent than ever.”

While not part of the official Biennale program, her exhibition, entitled The Horse Fell off the Poem after the eponymous poem by Mahmoud Darwish, is definitely part of the biennale gestalt.

As the IDF continued its merciless assault on Gaza, a recent demonstration in front of the Israeli and American pavilions organized by ANGA coincided with Mattar’s opening on April 17th. While Mattar was busy receiving art world luminaries, posters of her art, alongside other Palestinian artists including Raed Issa and Maryam Ali, were featured in the protests and plastered on Venetian walls. Biennale Director Adrian Pedrosa’s theme of “Foreigners Everywhere” has been transmuted into the Palestinian experience of exile and occupation.

The official collateral show SOUTH WEST BANK – Landworks, Collective Action and Sound focuses on works produced by artists, collectives and allies in and around the southern West Bank in Palestine. As organized by Artists + Allies x Hebron and presented in collaboration with Dar Jacir for Art and Research in Bethlehem, it aims to “strengthen the connection of expressions and cultural identities within changing urban and agricultural landscapes,” and to “share a voice centered on historical transmissions of memory and collectivity.” Indeed, my chat with Malak Mattar is interrupted by a surprise visit from Emily Jacir, part of the South West Bank group show happening, in that uniquely surreal Biennale global village way, just around the corner and over the bridge.

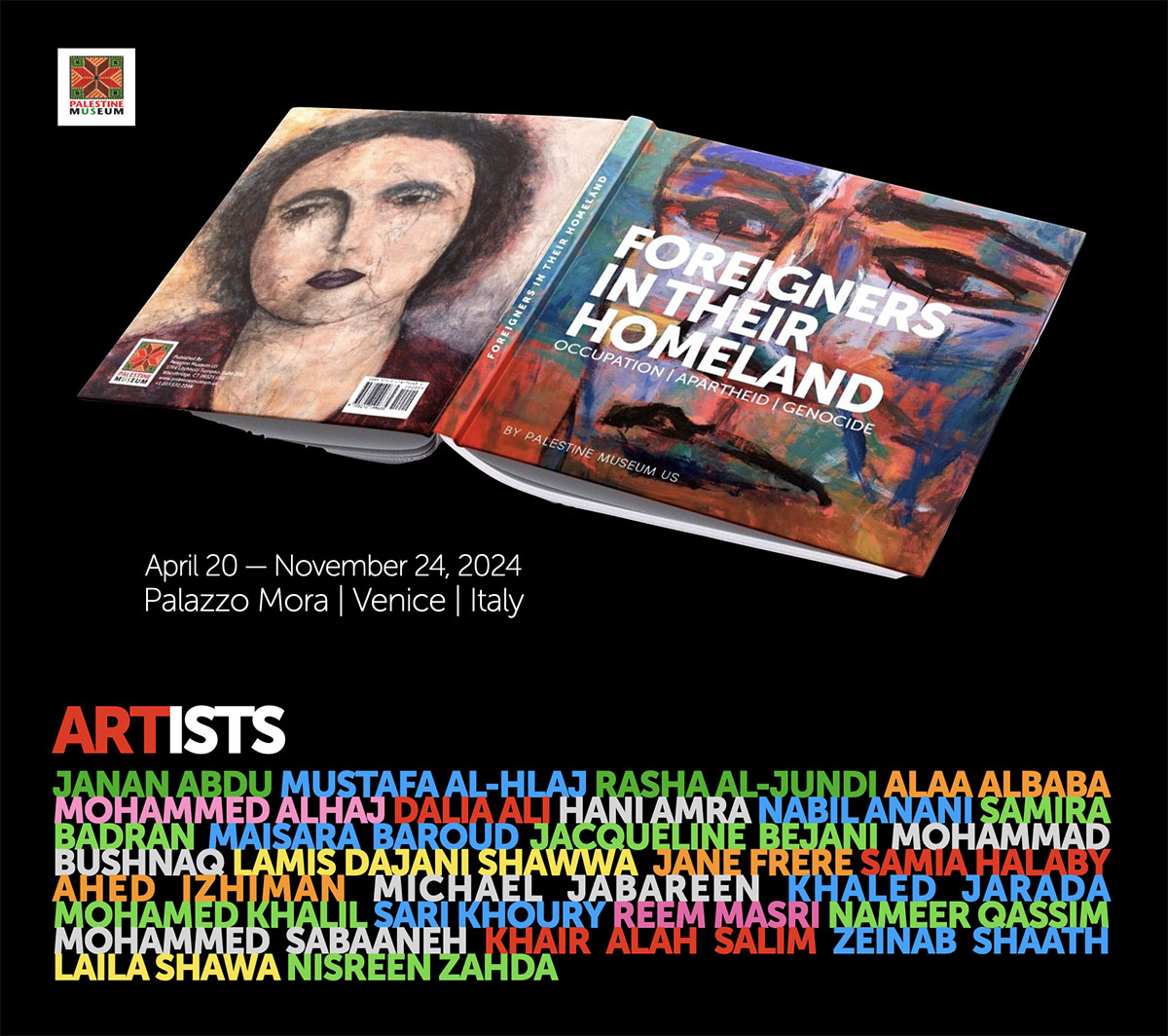

Not far from here either is the exhibition Foreigners in their Homeland: Occupation, Apartheid, Genocide, organized by the Palestine Museum US. Hosted at the European Cultural Centre’s historic Palazzo Mora, it features artworks ranging from world-renowned abstract artist Samia Halaby to new sketches by displaced Gazan artists produced in tents.

The recent opening of their exhibition — by far the most ambitious of the three — unfolds like a wedding, with Palestinian artists in diaspora joining in person, by Zoom, and, for those still living in tents in Gaza, in spirit. Samira Badran, whose work explores the notion of collective memory, the fragmentation of the body and the territory, barriers, and restrictions, is here in person. Attending by Zoom are Rasha al Jundi, Khaled Jarada and Michael Jabareen, who tells the assembled crowd, “This exhibition is about getting our voices out there. By presenting Palestinian art and stories, I hope these artworks will get stories stuck in your head and remain with you a long time.”

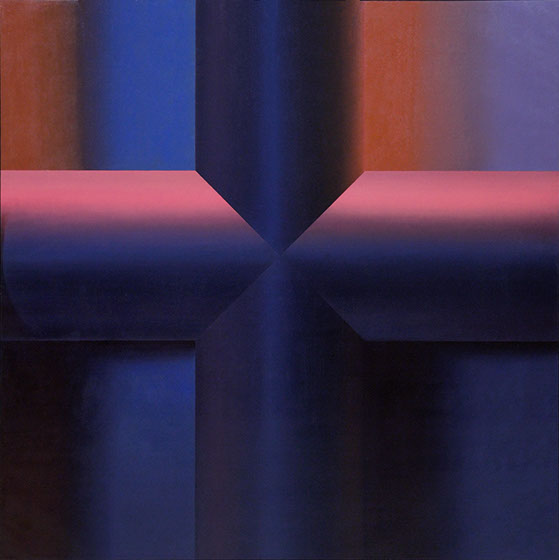

As guests — many wearing keffiyehs — pack the gorgeous gallery at the Palazzo Mora, a giant map of Palestine reimagined as a carpet, welcomes them. As in years past, many Palestinians come to look for their villages on the map. And yet, for all its success, this exhibition of 26 artists almost didn’t happen. Initially rejected by the biennale, the European Cultural Centre then stepped in to offer the historic Palazzo Mora as a hosting space. And esteemed artist Samia Halaby stepped up to offer one of the most significant works in the exhibition — a striking 1.24×3.83 meter acrylic on canvas painting titled “Massacre of the Innocents in Gaza.”

The day of the exhibition opening, her work “Black is Beautiful” went on to win a special mention from the biennale. In an Instagram post she dedicated her prize to the “press of Gaza,” saying, “The heroic youth of Gaza reporting visually, with their cell phones and their lives, the daily application of genocide have given human culture an invaluable and rare gift of collectively created work of documentary art. Its epic proportions are meaningful to Indigenous peoples everywhere reminding them of their own undocumented experiences.

“The targeted murder of more than 100 members of the Gaza press by Israeli forces with US backing has sparked international solidarity. Their work would make a magnificent pavilion for an international biennial of liberation.”

With so much unfolding in real time on the ground, narrowing down the entries into the exhibition required the wisdom of Solomon. While the Palestinian Museum US has a mission to represent the history and culture of Palestine through the arts, the question remained, as curator Faisal Saleh put it in his introductory talk at the opening: “How do you curate 75 years of occupation and 5 months of genocide?

“I didn’t want to have just the best work,” he went on, explaining his own parameters for designing the exhibition that will run through November 24th. “I wanted a mix of established and emerging artists.” Demographic and geographic diversity were also important factors; the show includes artists from the West Bank, from pre-‘48 Palestine, from Gaza as well as from those living in Syria, Jordan, and the US. Stylistic diversity was also considered: the show features abstract and figurative painting alongside sketches, sculptures, animation, and mixed media.

167.5×167.5 cm, 1969.

Four of the participating artists are deceased, including the late great Laila Shawa, whose iconic 2004 “Democracy in Red,” a 150x200cm work in acrylic, papier maché, gauze, nails, and metallic paint on canvas, features prominently in the exhibition. The artist and activist, described as the “mother of Arabic revolutionary art,” was born in Gaza City in 1940 and died in 2022 at age 82, leaving behind a legacy that included the Rashad Shawa Cultural Centre, which she founded in 1964. Shawa, whose brother attended the opening in Venice, forged elements of her country’s nature, folklore and architecture into compelling contemporary imagery that chronicled her nation’s plight. A multi-disciplinary artist, Shawa’s painting, photography, silkscreen prints, sculptures and installations powerfully expressed the struggles to liberate Palestine and Palestinian women. One of Palestine’s first contemporary artists to “crossover” into the West, her work graces the walls of the British Museum in London and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

Perhaps her best known 21st-century work is “Fashionista Terrorista” (2011). A screenprint of one of Shawa’s photographs, of a Palestinian fighter wearing a traditional keffiyeh decorated with a Swarovski crystal New York patch, speaks to the Western fetish for intifada as fashion statement. Her initial 1994 Walls of Gaza series incorporated both photography and text, employing images of graffiti spray-painted by the people of Gaza on the walls of their city, with one showing a child and a superimposed red circle called simply “Target.”

The choice of “Democracy in Red,” with its scarlet-tinged skulls and mutilated body parts nestled between prison bars, still speaks volumes. Paired with the Halaby work, the two grand dames of Palestinian art have a visceral and ceremonial presence here, ushering viewers into an exhibition that aims to encapsulate the Palestinian experience.

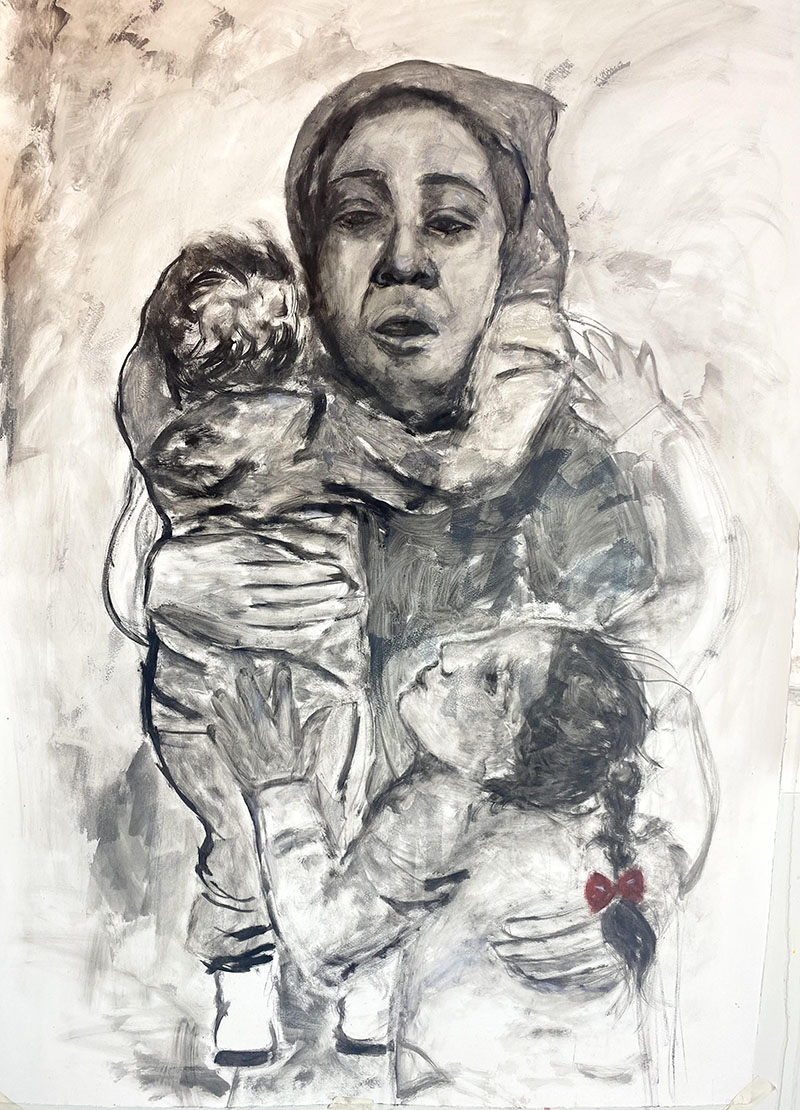

As Saleh introduces the show, he is framed by dozens of sketches produced by displaced Gazan artists living in tents, among them Mohammed al Haj and Maisara Baroud. Each sketch was printed on translucent paper and the light from the windows behind them literally and figuratively illuminates the Gazan experience. “This is the only artwork in Venice by artists in Gaza living in tents and starving with everyone else,” Saleh notes. “Each one tells the story of Gaza.”

The ghost of a painting by Mohammed al Haj that was destroyed by bombing before it could be smuggled out of Gaza has been reincarnated as a framed print at the back of the gallery. It depicts a series of phantom-like Palestinian farmers forlornly clutching shafts of wheat, framed by traditional mosaics and a blood-soaked sky. This is a show of survivor art, writ large.

“Palestinians, the native inhabitants of the land,” Saleh explains, “have tragically endured the label of foreigners on their land since 1948.” Near him, Zeinad Shaath’s 2018 acrylic on canvas painting of a deeply rooted olive tree draped in a keffiyeh, bears witness to his words.

The occupation of 1967, he says “deepened the foreignness through settlements and restrictions.” The work of the 26 Palestinian artists in the exhibition, he says “capture decades of struggle under the brutality of occupation — and a suffocating atmosphere that permeates every aspect of Palestinian life.”

A painting by Jerusalemite Ahed Izhiman, of a couple posing for their wedding photo in front of the Occupation Wall strewn with fairy lights, speaks to the normalization of this atmosphere. Beside it, Saleh Khaled Jarada’s 2023 charcoal on canson paper drawing of contorted Palestinian bodies internalizing and yet defying the ubiquitous concrete separation barriers of their occupation, looks on.

The exhibition, continues Saleh, depicts a “shredded homeland under threat of expulsion and erasure.” Nearby, a four-minute film by Nisreen Zahda using line art and 3D motion graphics portrays the “tattering of a once unified land into shards of territory.”

Saleh says the show “sends an urgent message — an SOS to the whole world.” But it also captures the hopes and “yearning for freedom” of the Palestinian people, he notes. A cartoon by award-winning caricaturist Mohammad Sabaaneh, depicting the daughter of the late Palestinian revolutionary Walid Daqqah who was conceived via sperm smuggled from his prison cell and artificially inseminated into his wife, when his Israeli jailers denied him conjugal visits, stares back in defiance.

But tonight is as much about celebration as it is about defiance. It’s a Venetian love-in for Palestinian art, and soon it’s time for a local student musical performance of traditional Palestinian songs. Zeina Barhoum, a young Palestinian woman singer arrives to entrance the rapt audience with love songs in Arabic and Italian.

As thousands of Gazans wait out an uncertain fate on the edge of the Mediterranean, these islands in the Adriatic send their love across the seas, offering up an artistic wedding in absentia, as a momentary antidote to funereal times.